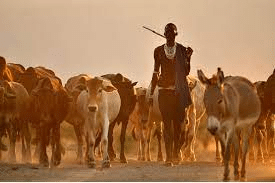

In the vast, sun-drenched savannas of East Africa, a scene unfolds that has been repeated for centuries – a herd of cattle, their sleek, muscular frames silhouetted against the endless horizon, moving in a graceful, synchronized rhythm across the land. This is the domain of the Masai, a people whose very way of life is inextricably linked to the well-being of their beloved cattle.

The Masai’s deep reverence for their cattle is more than just a matter of economic necessity; it is a cultural and spiritual cornerstone that has been passed down through generations. These majestic animals are not merely a source of sustenance and livelihood, but rather, they are seen as a reflection of the Masai’s connection to the land, their identity, and their place in the natural order of things.

At the heart of Masai pastoralism is the intricate and highly organized system of cattle herding. From a young age, Masai children are taught the intricacies of herd management, learning to identify individual animals, monitor their health, and guide them through the ever-changing landscape of the savanna. This knowledge is not just practical; it is a deeply ingrained part of the Masai’s cultural and spiritual inheritance, a way of understanding the world that is intimately tied to the rhythms of the land and the cycles of life.

The Masai’s cattle-herding practices are a testament to their profound understanding of the delicate balance between human needs and the preservation of the natural environment. They have developed a sophisticated system of grazing patterns and herd management that ensures the long-term sustainability of their pastoral way of life. By moving their herds across vast expanses of land, the Masai are able to minimize the impact on any one area, allowing the vegetation to recover and the ecosystem to remain in a state of dynamic equilibrium.

At the heart of this system lies the Masai’s intimate knowledge of their land and its resources. They have developed a deep and abiding connection to the natural world, understanding the subtlest of signs that can guide them to the best grazing grounds and the most reliable sources of water. This knowledge is not just a matter of practical survival; it is also a reflection of the Masai’s profound spiritual and cultural ties to the land they call home.

The Masai’s cattle-herding practices are also deeply rooted in their cultural and social structures. The herd is not just a collection of animals, but rather, a reflection of the Masai’s familial and communal ties. The ownership and management of the cattle are often organized along clan lines, with each family or sub-clan responsible for the care and well-being of a specific portion of the herd.

This sense of communal responsibility is central to the Masai’s way of life, and it is reflected in the intricate rituals and ceremonies that surround their cattle-herding practices. From the elaborate blessing ceremonies that mark the birth of a calf to the solemn rites of passage that accompany the transition from childhood to adulthood, the Masai’s relationship with their cattle is imbued with a profound spiritual and cultural significance.

Yet, in recent years, the Masai’s pastoral way of life has faced a number of challenges, as the forces of modernization and environmental change have begun to impact the delicate balance of their traditional way of life. Encroachment on Masai lands, the dwindling of grazing resources, and the shifting patterns of rainfall have all contributed to a growing sense of uncertainty and anxiety within the Masai community.

Despite these challenges, the Masai have remained steadfast in their commitment to their pastoral traditions. They have embraced new technologies and techniques that can help them adapt to the changing realities of the modern world, while still maintaining the core values and practices that have sustained their way of life for centuries.

As the world continues to evolve, the Masai’s cattle-herding practices stand as a testament to the enduring power of cultural tradition and the deep, abiding connection between human beings and the natural world. In the hoofprints that trace across the endless savannas, we see the imprint of a people who have learned to walk in harmony with the land, their every step a reflection of a wisdom that has been forged over generations of struggle, adaptation, and resilience.