Improving education on the African continent has been a cornerstone of international aid for centuries. Though it does depend on the state, billions are channeled to build schools, train teachers, and provide the necessary materials for learning. Therefore, the intention remains unmistakable: to fix some of the greatest challenges facing the continent’s education systems. But despite the best of efforts, one question remains whether such kind of aid has been more help or hindrance.

The Case for Assistance

On the plus side, international aid does indeed continue to be a factor in developing educational access on the continent. Indeed, many of the schools that have been built in rural areas are thanks to funding provided through international organizations. Programs such as UNICEF’s Education for All initiative have helped raise enrollment rates, especially among girls, who are too often hindered from attending school owing to cultural or economic reasons.

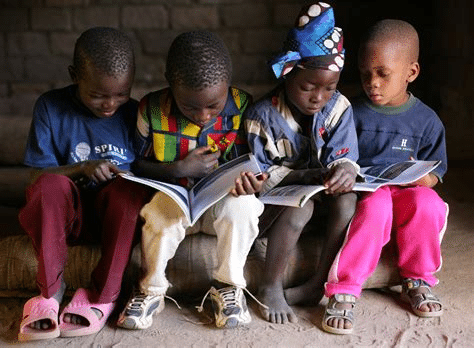

In fact, foreign aid has facilitated various training programs for teachers and has also provided the much-needed resources, such as textbooks, to make education more accessible and mainstream.

Additionally, in humanitarian crises or natural disaster zones, emergency aid plays a very crucial role when the educational infrastructures are usually destroyed. In these cases, international funding makes sure that displaced children continue their education either in refugee camps or temporary learning centers, consequently reducing the long-lasting impact of disrupted education.

The Case for Hindrance

But there is also a darker side to aid. One of the more major criticisms of aid is that it tends to create dependency. Indeed, many African countries have become heavily dependent on foreign funding to support their education systems. When shifts in donor priorities reduce or redirect international funding, schools and programs often collapse, underscoring the lack of locally owned and sustainable solutions.

In addition, assistance does not align with the needs on the ground. The donor agencies themselves may be driven by projects that deliver results that also address strategic objectives, rather than community-specific challenges. For example, technology-related projects generally praised worldwide-for example, introducing laptops to students-often do not work in communities without even basic infrastructure in place, like electricity or internet connectivity.

Corruption and mismanagement also pose great barriers to improvement. Money meant for enhancing education can be lost to bureaucratic inefficiency or frank theft, thus draining the effectiveness of the aid and sapping public confidence.

Striking a Balance

If international aid is to help reform African education effectively, the operations should aim at long-term sustainability and local empowerment. Collaboration should be in place with governments, communities, and educators for the assurance that assistance addresses the real needs and builds up local capacity. Investment in teacher training, curriculum development, and robust education policies can enable systems less reliant on external funding.

Besides, transparency and accountability mechanisms should be strengthened to avoid misappropriation of funds. Donors should also take into consideration that realities differ between the countries of Africa, therefore allowing their approaches to reflect cultural, social, and economic differences.

Conclusion

International aid can indeed serve as a real catalyst for change in African education, provided its deployment is properly effected. Moving away from the ‘one-size-fits-all’ philosophy, prioritizing sustainability and local ownership, it will turn from the necessary evil to a spur for enduring reform. Only then can the people of Africa truly own their own education systems and ensure a better future for their children.