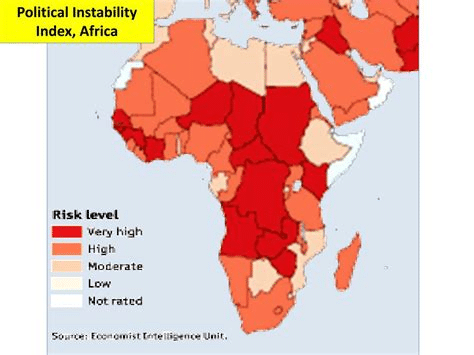

Political instability has been the bane of too many African nations for quite a long time, and this happens in almost all other sectors, but none more than that of education. Many challenges persist, from disrupted schooling to misallocated resources. Understanding how political instability undermines the education sector holds the key to addressing these persistent problems and paving the way for progress.

Disruptions to Learning

Widespread disruption to schooling usually emanates from political instability. Where there is conflict in a country or where the rate of change in government occurs quite frequently, schools are usually shut down, damaged, or even destroyed. Large swathes of children in areas like Somalia, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo have been displaced by armed violence, leaving them without a home or regular schooling. Teachers flee; resources get spent, and students have disrupted learning, sometimes for years.

Political uncertainty, even when instability has been less severe, has frequently led to strikes by teachers and school staff as governments cannot pay salaries or accurately budget funds. This inconsistency creates gaps in education and erodes the quality of instruction, leaving students unprepared for the challenges they face.

Financial Mismanagement

With political instability comes corruption and mismanagement of public resources, apparently, having huge, destructive effects on education. Funds that should be spent on schools, teacher training, and infrastructure development are diverted to either deal with immediate political crises or to private bank accounts through corrupt dealings. Lack of accountability ensures scarce resources do not reach schools or students.

Moreover, education budgets usually possess the least priority in unstable governments, which give more priority to military needs and other urgent needs. Some results of this misallocation include crowded classrooms, a shortage of learning materials, and poorly maintained facilities compromising the learning environment.

Brain Drain and Teacher Shortages

The existence of instability therefore becomes a factor of dissuasion, not only of students but even of qualified teachers. Teachers abandon dangerous and unstable territories or countries to seek out safer pastures, further worsening the already alarming brain drain. Already-fragile education systems thus have to struggle with the scant presence of skilled professionals-a fact that lowers the quality of education even more.

Besides that, political instability typically dissuades foreign investment in education, as well as international aid. In fact, the problem of governance usually tends to deter donors, as they do not like investing in systems that may collapse or fail to deliver proper outputs, thereby depriving the sector of much-needed external support.

Long-term effects

Besides being immediate, the effects of political instability on education are very long-lasting. Generations of children who miss out on quality education because of instability grow up without the requisite skills needed to contribute meaningfully to their economies, perpetuating cycles of poverty and underdevelopment. As a matter of fact, uneducated youth are more likely to be drawn into conflicts or exploited by political factions, thus a vicious cycle of instability is created.

Toward a Solution

In trying to break this vicious circle, a multi-layered approach is necessary. First, governments and international bodies need to recognize peacebuilding and political stability as prerequisites to increasing education scope. Investments in education during stable periods should be oriented toward resilience, such as construction of infrastructure that could resist conflict and creating systems to support the learning of displaced individuals. It is equally attractive when local communities and civil society come forward.

Their voice, demanding more transparency and accountability, contributes much to the better spending of education funds, even in the most politically unstable contexts. In line with this, international donors should continue to link their aid to measurable impacts of the different interventions so that governance reforms go hand in hand with educational progress.

Conclusion

While much improvement has been observed, political instability remains a significant barrier to educational development in Africa. Thus, by addressing the very root of its causes and prioritizing system resilience, governments and stakeholders will be effectively shielding the right to education, even in the worst scenarios. The true development potential of the education sector in Africa can be unlocked only when it constructs a better future.