You probably cross rivers every day without realising it. Beneath the concrete underfoot are culverts – tunnels installed under roads and railways that allow rivers to pass from one side to the other. Like bridges, culverts allow people to cross rivers, but unlike bridges, culverts often don’t allow the fishes living in those rivers to cross roads.

Why worry about fishes crossing roads? A recent study found that, on average, the abundance of 247 migratory fish species has fallen by 76% worldwide since 1970. The hundreds of thousands of dams that fragment rivers around the world are a major cause of these declines. Removing these dams, the report urged, could restore the pathways that migratory fishes take and help their populations rebound.

But dams are just the tip of the iceberg. Culverts are smaller, and far more ubiquitous and concealed. While scientists can track the locations of dams built around the world with satellites, culverts are hidden under roads, making it difficult to map them. Throughout Europe, culverts can be found under houses, shops and entire villages.

Culverts limit the movements of migratory fish like the critically endangered European eel, disrupting their access to food and spawning areas. When fish are blocked from making these essential journeys, entire freshwater ecosystems suffer. Predators go hungry and flows of nutrients between lands, rivers and seas are severed.

Culverts cover continents

In the Great Lakes of North America, we estimate that there are at least 250,000 road culverts installed on rivers. That’s 35 times more than the number of dams in the region.

Culverts are also common across the Brazilian Amazon. Where deforestation increases and new farmland is created, culvert construction increases too. Throughout Amazonian streams, makeshift river crossings and poorly installed culverts prevent fishes from foraging and spawning. One small tributary of the Amazon is estimated to have 10,000 of these crossings.

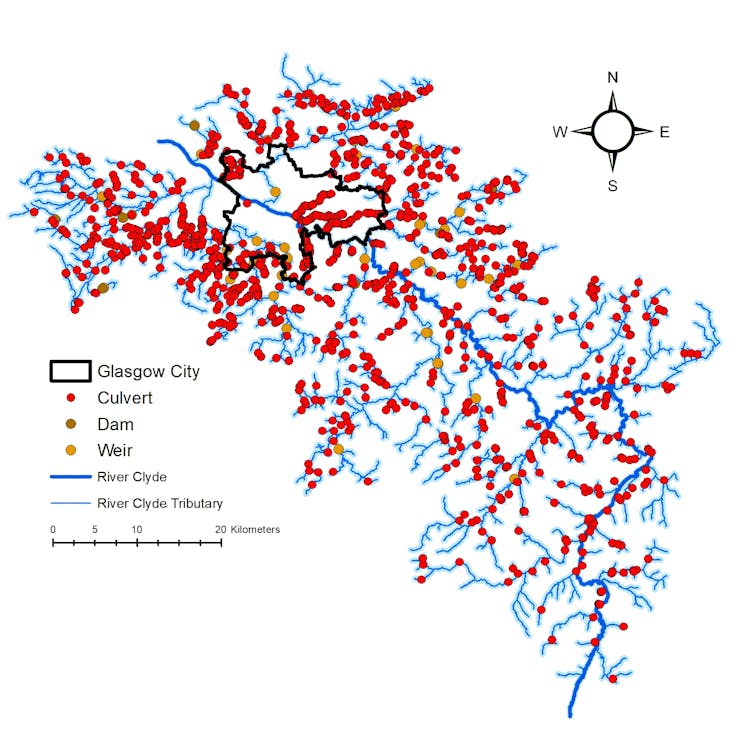

In Scotland, a recent study found that there are, on average, 12 kilometres between adjacent dams and weirs on any given river. Yet our research team found nearly 1,500 culverts on the River Clyde and its tributaries – that’s roughly 29 times more frequent than dams and weirs, translating to one culvert for every one and a half kilometre of river. You can see this on the map below. Great Britain has some of the highest road densities on Earth, and so the true scale of river fragmentation by roads and culverts could be much higher.

Culverts, dams and weirs on River Clyde

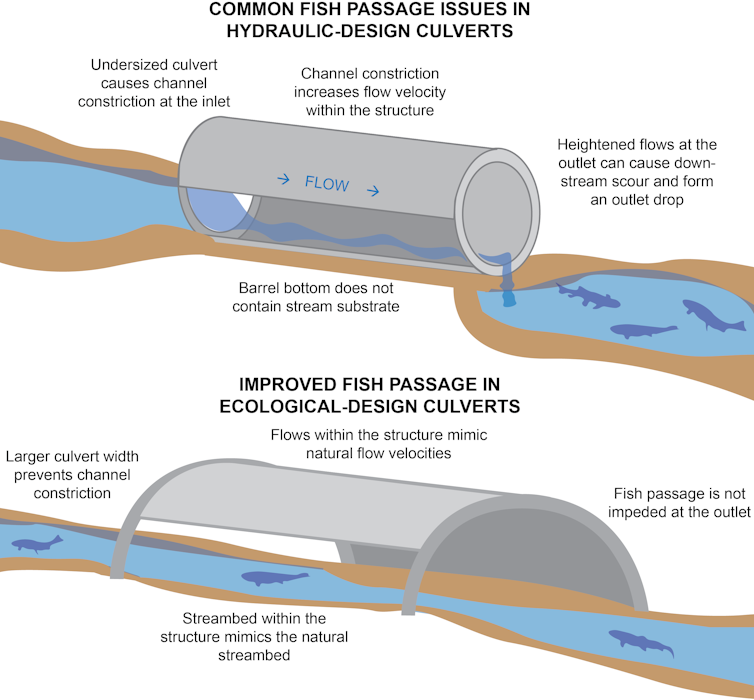

Ensuring rivers and species can remain connected hasn’t been a priority in the design and installation of culverts to date. Hydraulic culverts like the one in the lead image are among the most prevalent designs used worldwide. Their design constricts river channels and speeds up water flow, with the aim of allowing as much water as possible to pass through during floods.

But this design can result in a culvert becoming “perched”, forming a mini waterfall on the downstream side of the structure. Perched culverts can prevent fishes from swimming upstream, cutting short their migration and stopping spawning.

Helping fishes across roads

Bridges are better than culverts for allowing fishes to cross under roads or railways. Yet not all culverts are bad for nature. Culverts designed with rivers in mind are wider and offer more natural gradients, helping water and animals to move more freely. Replacing hydraulic culverts with ecological designs, per the diagram below, can not only restore fish migrations. It can also reduce the risk of flooding, and lower repair and replacement costs.

Governments must establish laws that ensure anything built in rivers allows water and species to move as freely as possible. Indigenous nations in the US compelled lawmakers in Washington state to repair or replace any culverts that failed this test. As a result, responsible agencies are establishing new rules to ensure anything built in state waters does not negatively affect habitats.

Structures like culverts must be adaptable to keep species moving, even as climate change causes river flows to change. But when planners decide to build new roads in most other places worldwide, the consequences for rivers and fishes are rarely considered.

As road networks expand to connect more of the world, we urge governments to better regulate the design of culverts that intersect these routes. Only by ensuring that fishes can cross roads can we hope to reverse the steep declines that our construction habits have wrought.

Source: The Conversation