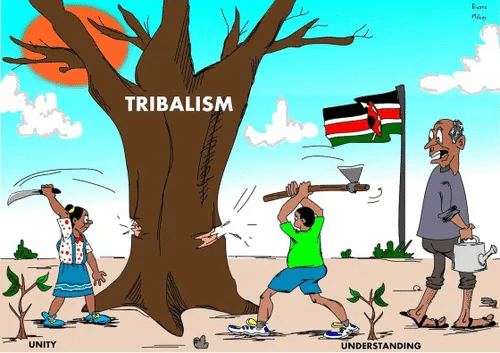

In a nation as diverse as Kenya, where over 40 distinct ethnic groups call this land home, the promise of a meritocratic, equitable job market should be a cornerstone of the country’s social and economic fabric. Yet, as countless Kenyans have discovered, the reality on the ground paints a far more troubling picture – one where the insidious forces of tribalism and nepotism continue to hold sway, undermining the principles of fairness and eroding the public’s faith in the system.

“It’s an open secret that the playing field is not level,” says Fatima Njoroge, a job seeker in Nairobi. “No matter how qualified you are, if you don’t have the right connections or the right ethnic background, your chances of getting hired are significantly diminished.”

Njoroge’s experience is echoed across the country, as Kenyans from all walks of life recount the frustrations of navigating a job market that is often more concerned with ethnic allegiances and personal relationships than with the merits and qualifications of the applicants.

“Tribalism and nepotism have become deeply entrenched in our employment practices,” explains Dr. Esther Wangui, a sociologist at the University of Nairobi. “They permeate every aspect of the process, from hiring and promotions to the allocation of resources and opportunities. And the consequences are far-reaching, undermining social cohesion, eroding public trust, and stunting the country’s overall economic and social progress.”

The roots of this challenge can be traced back to the country’s turbulent history, where the legacies of colonial rule and post-independence power struggles have fostered a culture of ethnic favoritism and the concentration of resources within the hands of certain dominant groups.

“It’s a complex, multifaceted issue,” says Dr. Wangui. “Tribalism and nepotism didn’t just emerge out of nowhere – they are the product of a long, painful history of systemic discrimination, political maneuvering, and the unequal distribution of power and opportunity.”

This dynamic has become increasingly evident in the public sector, where the influence of tribal affiliations and personal connections can often supersede the principles of meritocracy and equal opportunity. From the allocation of government jobs and contracts to the distribution of development projects and resources, the specter of tribalism and nepotism casts a long shadow over the very institutions that are meant to serve the interests of all Kenyans.

“When you see certain ethnic groups dominating the upper echelons of the civil service or the leadership of key state-owned enterprises, it’s a clear indication that the system is rigged,” says Njoroge. “And it’s not just a matter of fairness – it’s a matter of national security and social cohesion, as the disparities and resentments it fosters can and have led to conflict and instability.”

The private sector has not been immune to these challenges either, with many Kenyan businesses and corporations accused of perpetuating the cycle of tribalism and nepotism in their hiring and promotion practices. The consequences, experts say, are far-reaching, not just for the individuals who are denied opportunities, but for the broader economy and the country’s global competitiveness.

“When you restrict the talent pool and limit opportunities based on ethnicity or personal connections, you’re essentially handicapping your own workforce,” explains Dr. Wangui. “You’re missing out on the diverse perspectives, the innovative ideas, and the passionate, qualified individuals who could be the driving force behind your organization’s growth and success.”

To address these deep-seated issues, the Kenyan government has enacted a range of policies and initiatives aimed at promoting greater inclusion and transparency in the job market. From the establishment of anti-discrimination laws to the implementation of affirmative action programs, these efforts have sought to level the playing field and ensure that all Kenyans have a fair shot at securing meaningful employment.

“The political will to tackle this problem is there, but the challenges are formidable,” says Njoroge. “Deeply entrenched power structures, vested interests, and the persistence of a culture that prizes tribal loyalty over meritocracy – these are not easy obstacles to overcome.”

Yet, as the country grapples with the mounting social and economic consequences of tribalism and nepotism, the call for change has never been more urgent. Experts and civil society leaders alike are calling for a concerted, multi-pronged approach that combines legislative reforms, public education campaigns, and the empowerment of independent oversight mechanisms to hold both the public and private sectors accountable.

“This is not just about fairness and equity – it’s about the future of our nation,” concludes Dr. Wangui. “By dismantling the barriers of tribalism and nepotism, we can unlock the true potential of our people, foster greater social cohesion, and build a more prosperous, inclusive Kenya that works for everyone, regardless of their ethnic background or personal connections. The time for action is now.”

As Kenyans confront this persistent challenge, the path forward may not be an easy one, but the rewards of success are immeasurable. A job market free from the shackles of tribalism and nepotism – one that rewards merit, diversity, and the collective aspirations of the Kenyan people – holds the promise of a more equitable, resilient, and dynamic society, poised to thrive in the face of the 21st century’s most pressing challenges.