In February 1974, foreign ministers of member-states of the Organisation of African Unity met in Addis Ababa. Top of their agenda: the twin problems of the situation in the Middle East and the impact of the spiralling price of oil. As the ministers began proceedings, however, the streets of the Ethiopian capital were rocked by popular demonstrations and disorder triggered by the government’s mismanagement of the ongoing famine and an economic crisis. The armed forces took up positions around the city. In their alarm, the Ethiopian hosts declared that they could no longer guarantee their guests safety and abandoned the OAU meeting. The situation swiftly deteriorated: waves of strikes opened space for military intervention. By September, Emperor Haile Selassie’s sweeping ancien régime had been swept away.

The sudden departure of the diplomats and the anger on the streets of Addis Ababa brought to the fore the global and local dimensions of the first ‘oil shock’. Between the outbreak of hostilities in the Middle East in October 1973 and the OAU conference, the price of oil had risen by a factor of four. While the immediate cause for these price rises was an Arab response to the Yom Kippur War, they built on a longer campaign by oil producing states to seize command of their petroleum reserves under the banner of ‘resource sovereignty’. Members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries had wrested control of the strategic hydrocarbons from Euro-American multinationals. Cheap oil had been the lifeblood of the three decades’ long post-WW2 economic boom in the Transatlantic world. Now the Third World’s petroleum exporters sought to capitalise on their hydrocarbon wealth in dramatic fashion.

Their intervention created panic in the industrialised world. The United States was singled out for its support of Israel and targeted by an ‘embargo’. But the embargo was easily circumvented, short-lived, and only imposed by Arab exporters (there was no ‘OPEC embargo’, despite the term gaining common currency). Yet while shortages – real or imagined – in the West dominated headlines, the oil importing states of the Third World felt the effects of price rises hardest. The crisis increased petroleum bills, drained foreign exchange reserves, and reduced export demand for raw materials. It compounded existing challenges to agrarian economies posed by shortages of fertiliser and the catastrophic impact of El Niño drought across the Sahel Belt. A global food crisis became entwined with a global energy crisis.

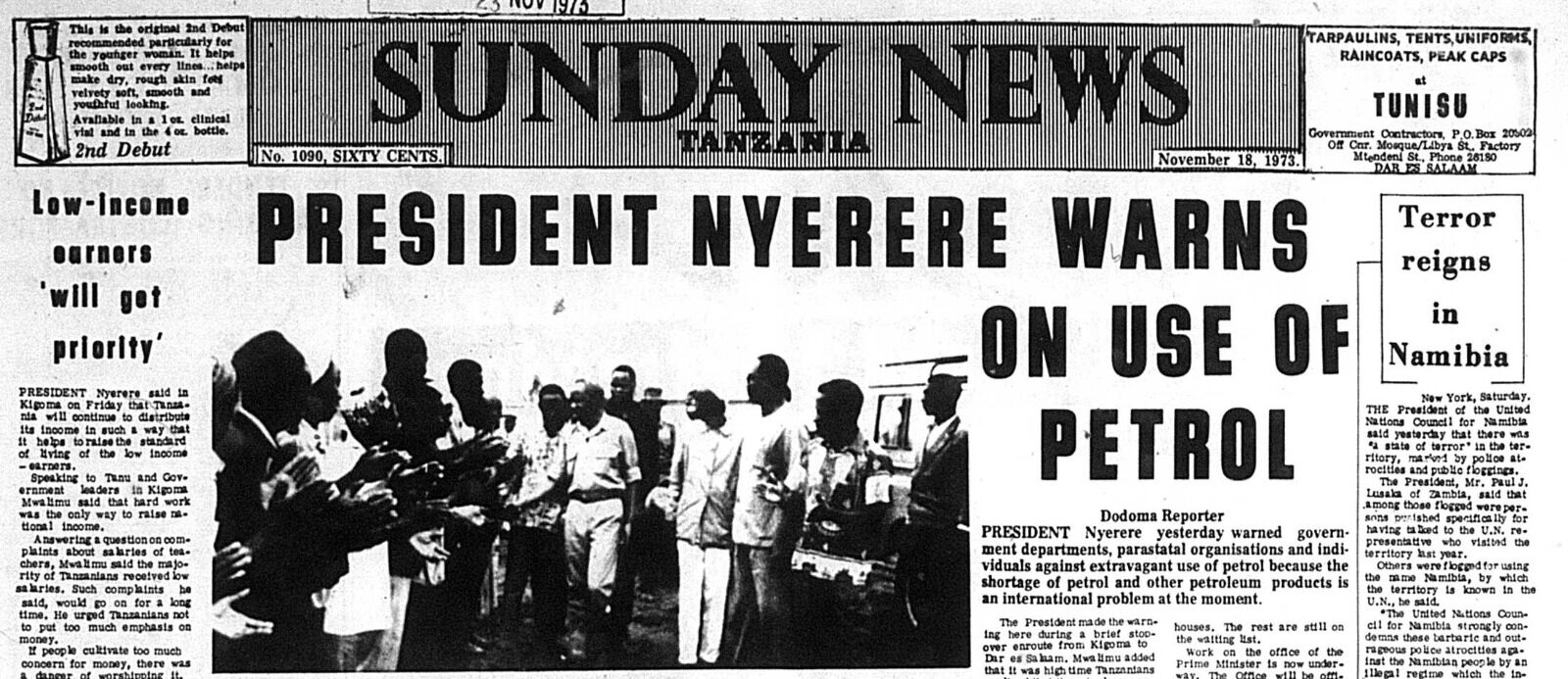

This perfect storm exposed Africa’s vulnerability to external economic shocks. Among independent states south of the Sahara, only Nigeria and Gabon exported petroleum. Access to oil had underwritten the ambitious, creative state-making projects that had characterised the post-independence decade. For all post-colonial governments had talked up the importance of self-reliance, their visions for agrarian revolution or heavy industrialisation ran on oil. The underdevelopment of rail and marine transport infrastructure made African economies also highly dependent on motor transport, powered by petroleum. A report produced by the Bank of Tanzania to a continental meeting of central banks projected that the oil import bill of non-producing African countries would rise from $516 million ($3,85 billion in 2024) in 1972 to $2,063 million in 1974 (about 12.8 billion in 2024).

Even in Ghana, which produced just one percent of its electricity from oil thanks to its investment in hydroelectric schemes, the instability in global commodity prices which rippled through the 1970s posed serious questions of state budgets. Regimes across the continent confronted the challenge of balancing short-term stability against long-term development growth. The tools they had at their disposal for fighting the shock – subsidies, fixed prices, import controls, currency revaluation – all involved trade-offs in priorities. Governments became increasingly interventionist in the day-to-day running of their economies, but without the resources to meet the welfare demands of rapidly growing populations.

If we can look beyond the attainment of formal political independence as a key caesura in Africa’s contemporary history, then the oil shocks of the 1970s and the turbulence in commodity prices which accompanied them represent an alternative turning point. Even allowing for their very different goals, there had been much continuity between postwar development plans designed to prop up flagging empires and the emancipatory projects of the post-colonial regimes which succeeded them. Whereas conventional narratives foreground the impact of externally imposed structural adjustment policies on Africa as a watershed, this obscures the degree to which African states had already experimented with ad hoc measures and reconsidered development plans in the 1970s. Critical here is the need to focus on African responses to commodity shocks and the choices which were on the table. For sure, the structural legacies of colonial rule, maintained through relations of economic dependency, left African states among the most vulnerable to global shocks. But they were never simply helpless victims to dynamics totally outside of their control.

By the early 1970s, the lustre of political independence had worn off, as the economic limits to decolonisation became all too clear. African economies remained either in the hands of foreign capital or trapped in cycles of neocolonial dependency. In fora like the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, they had developed a powerful critique of global inequalities. When Arab members led their OPEC allies in hiking the price of oil in October 1973, African states celebrated. In a flash, OPEC had put this anticolonial economic logic into action in stunning fashion. It emboldened broader Third World attempts to restructure the global economy. In May 1974, the UN General Assembly called for a ‘New International Economic Order’, which would redress the growing North-South divide in the global economy.

The events of late 1973 appeared also to demonstrate the potential for Third World unity against continued colonial occupation. Many African states had already severed their diplomatic relations with Israel following the Six-Day War of 1967, but the Yom Kippur conflict prompted twenty further countries to follow suit. The Palestine Liberation Organisation expanded its presence in the continent, opening an office among the liberation movements headquartered in Dar es Salaam. The Arab world declared their solidarity with liberation struggles in Africa, extending the embargo against the United States to Portugal, Rhodesia, and South Africa. The actions of OPEC’s oil elites seemed to have re-energised the Third World’s anticolonial project by harnessing together its economic and political agendas.

As their vulnerability to the shocks became clear, there was a widespread expectation among African states, born from a mixture of principled solidarity and a tactical quid-pro-quo, that Arab exporters would supply oil at discounted prices. The OAU established a ‘Committee of Seven’ on the petroleum question, which toured Arab capitals seeking to translate Third Worldist political solidarities into meaningful assistance to tackle the crisis which OPEC had created. Arab delegations made similar reciprocal visits. Ultimately, such trips proved little more than photo opportunities on airport tarmacs, as African hopes for preferential oil prices went unfulfilled. Surveying the situation, the OAU described ‘a period of bitter disappointment – a period of loneliness among friends’.

The frantic search for oil soon claimed a high-profile victim. In June 1974, OAU secretary-general, the Cameroonian Nzo Ekangaki resigned, resigned when it came to light that he had signed a contract with Lonrho, a multinational with stakes in white-minority-ruled southern Africa, which made the firm the exclusive consultants for any member-state seeking assistance to import petroleum. The appointment of Ekangaki’s successor at the OAU’s annual heads of state summit in Mogadishu became an acrimonious affair, as African-Arab tensions again rose to the surface. Yet the Ekangaki affair, alongside the OAU’s own inquiries, also drew attention to the diplomatic limits of attempts to resolve the crisis between national governments. The global oil economy was a murky world, involving opaque networks of tanker fleets, commodity dealers, and multinational petroleum firms. Having had their operations nationalised in oil producing countries, the latter now sought to carve out new profits from activities in shipping, refining, and distributing oil. Nationalising production at oil wells had only increased the multinationals’ stakes for control over downstream supply chains.

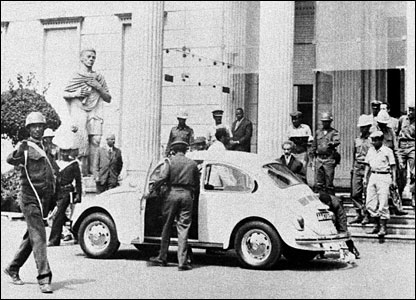

As the cost of the crisis took effect, Africa’s new petropolitics spilled out into the streets. Governments were forced to decide on where the cost of the burden of rising oil bills should fall: on the state, businesses, or ordinary people. In Ivory Coast, the government chose the latter and increased the price of bus tickets by sixty percent. In Ethiopia, which was already ravaged by the state mismanagement of El Niño famine, the state announced a fifty percent hike in fuel prices. In anticipation of the measure’s impact on ordinary Ethiopians, it warned private transport providers against passing this increase on to passengers. In response, taxi owners in Addis Ababa called a strike. As Semeneh Ayalew Asfaw has shown, the strike not only paralysed the city’s economy – the absence of a public transport network reflected the lack of investment in public services under Haile Selassie – but also catalysed political dissent. Teachers and students protested at inflation, creating the conditions for the disorder that sent the OAU delegates rushing to the airport.

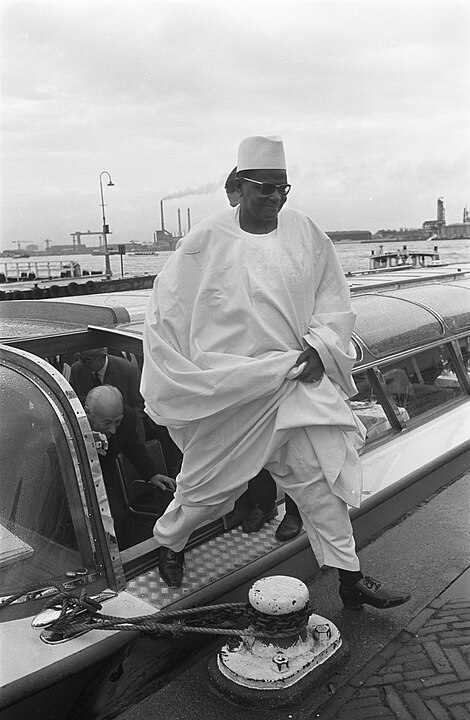

Even if the collapse of Ethiopia’s creaking monarchy was perhaps a case apart, it offered a parable for ruling elites elsewhere. In Niger, another drought-ravaged state, Hamani Diori had sought to capitalise on the example set by OPEC to renegotiate the sale of its strategic uranium resources to France, especially considering expanding interest in nuclear energy as the oil crisis took hold in Europe. Diori had proposed to index the sale of uranium to the rising price of oil. But these efforts were stopped in their tracks in April 1974, when Diori was overthrown in a coup d’état by soldiers who exploited Niger’s dire economic situation. Neither the fall of Haile Selassie nor Diori was solely the consequence of the crisis. But they demonstrated how regimes that struggled to meet citizens’ demands could be pushed over the edge by the oil shock.

Inspired by the OPEC states’ resource nationalism and driven by Niger’s increasingly dire economic situation, President Hamani Diori’s efforts to renegotiate the price of uranium with France led to his ouster via a military coup in 1974. Photo by Ron Kroon for Anefo

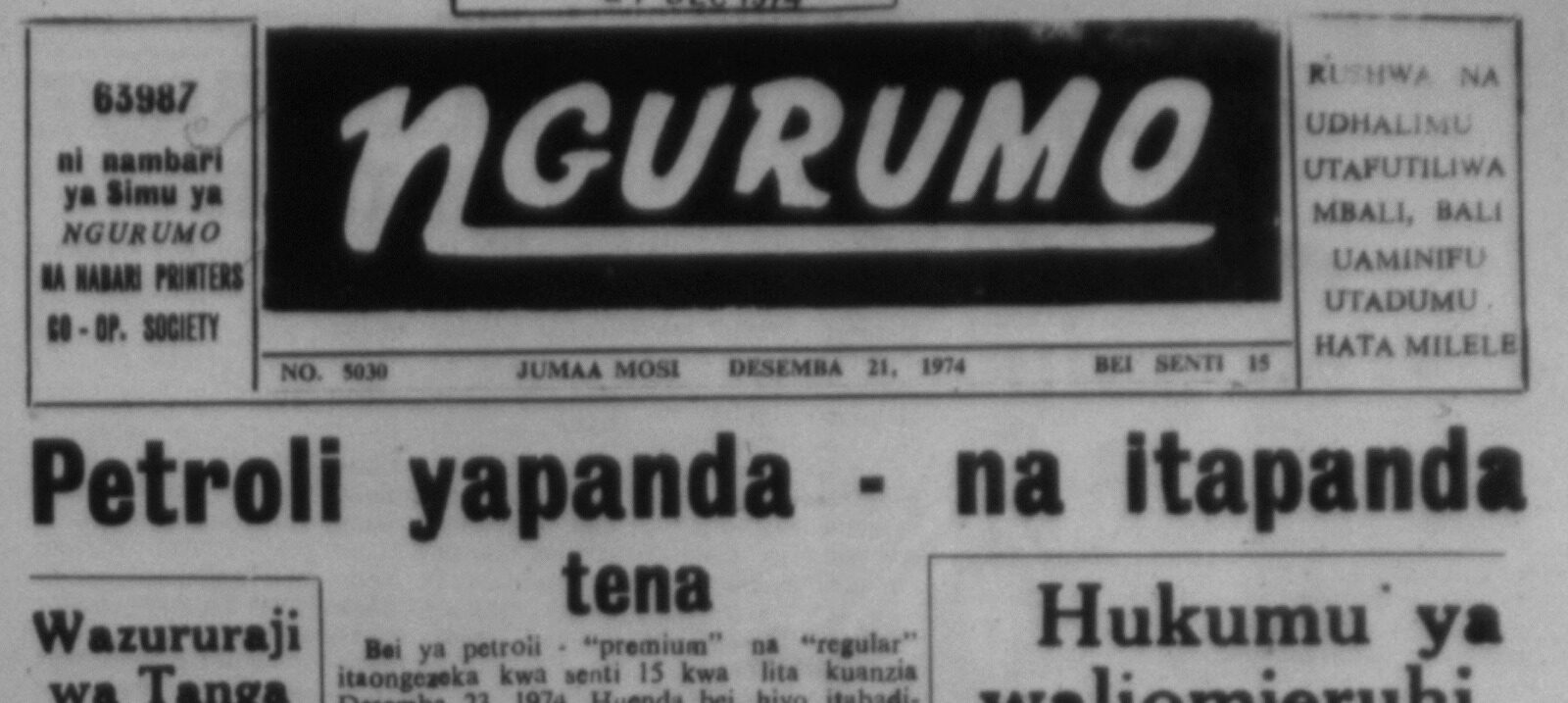

For most states, the political consequences of the oil crisis were less explosive. But African governments’ responses to commodity shocks had profound consequences for social contracts established in the heady years of independence. Post-colonial governments had raised expectations of growth and development – horizons which now seemed to be receding rapidly. The sudden onset of inflation brought a sense of bewilderment for citizens, as did the government’s firefighting measures to arrest it. ‘Juu!! Juu!! Juu!! Juu!!’ exclaimed the front page of Nairobi’s Baraza newspaper – ‘Up! Up! Up! Up!’ – as Kenya’s minister of finance, Mwai Kibaki announced across-the-board rises for consumer goods in June 1974. ‘In the city, we’re under siege, the price of everything is rising’, began a reader’s poem to Tanzania’s Ngurumo, reeling off the shocking cost of consumer goods in Dar es Salaam. From the marketplace to the boardroom, debates raged about subsidies and fixed prices, as consumers and producers argued about changing priorities in a new era of scarcity. Accusations about smuggling and hoarding proliferated, giving expression to simmering tensions among communities about who had enjoyed the fruits of independence at the expense of the working poor.

In the medium-term, snap decisions taken to keep economies afloat had consequences. While the advocates of structural adjustment in the 1980s blamed Africa’s economic travails on corruption and mismanagement, research in the archives of the continent’s ministries of finance has demonstrated a general under-appreciation of the impact of the external shocks of the 1970s on growth. Yet the challenge of such number-crunching is that it is difficult to untangle structural conditions from political responses. There were certainly still choices on the table: as a recent study shows, the growing gap between official and unofficial exchange rates in Accra during the crisis years led to declining outputs from cocoa farmers whose export earnings had increasingly little purchasing power. Instead, they turned to smuggling out cocoa through neighbouring countries. In Kenya, on the other hand, a more flexible approach towards foreign exchange controls enabled the state to continue to benefit from income from both domestic and regional coffee exports during a mid-1970s boom in global prices.

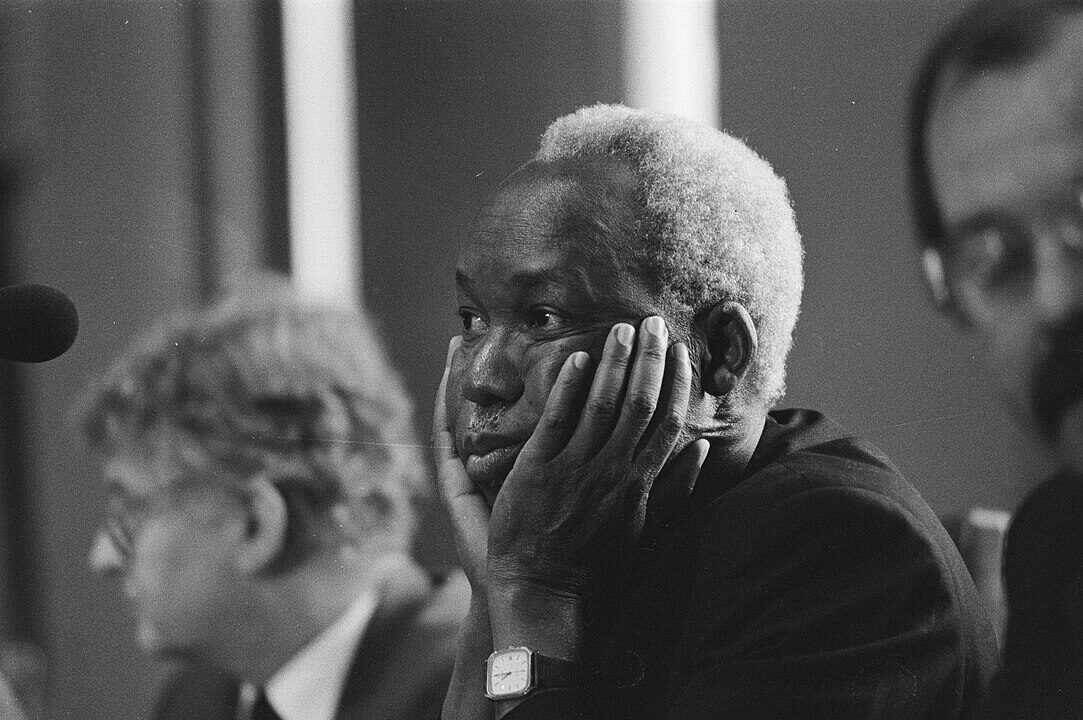

Other African governments reconsidered post-colonial development plans whose limits had been exposed by the oil shock. Tanzania edged away from the emphasis on rural transformation which had characterised ujamaa socialism. By the time of the oil crisis, the Harvard-trained economist Justinian Rweyemamu had emerged as the country’s leading advocate for turning towards industrialisation. Tanzania’s third development plan, delayed by two years to 1976 as the government sought to plot a direction forward in a rapidly changing world, set out a ‘basic industrial strategy’, using the country’s natural resources to manufacture import substitutions. As historian Emily Brownell has argued, the Tanzanian government sought to ‘re-territorialize the future’: maximising the use of alternative materials from within the country to reduce foreign exchange burdens. This filtered through to the level of the household economy: in place of cement, which was manufactured through an energy-intensive, oil-based process, the Tanzanian government urged citizens to produce mud bricks in kilns fired by locally sourced charcoal.

Such measures could do little to alter the fundamental challenges faced by states where the structural legacies of colonialism left them dependent on commodities which suffered falling or capricious demand in the aftermath of the oil crisis. Zambia, where ninety percent of foreign exchange earnings came from copper, experienced the short-lived benefits of a temporary upturn in mineral prices in response to the oil shock. But a subsequent collapse in copper demand caused by the global industrial downturn sent the national economy into a tailspin. Hopes that the Intergovernmental Council of Copper Exporting Countries could reproduce OPEC’s success were disappointed, as prices proved much more elastic and coordinating the interests of members who included Zambia and Zaire, alongside Australia, Chile, and Yugoslavia, proved impossible. Like Diori’s ill-fated initiatives in uranium dealing, OPEC’s solution proved an exception to the rule, as power remained firmly in the hands of the industrialised nations.

New forms of international cooperation proved false dawns. African governments looked to the nouveau riche Arab petrostates as new development partners. In 1977, Cairo hosted the first Afro-Arab Summit Conference, which adopted a charter for transregional cooperation. But while they issued declarations of solidarity at the rostrum, African politicians grumbled in conference corridors about an Arab betrayal. Various sources of support – the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa, the OPEC Special Fund, and other initiatives – provided scant relief. The ‘Afro-Arab moment’ proved short-lived.

Responding to demands for discounted oil from its neighbours, Nigeria vacillated between answering calls for pan-African solidarity and fulfilling its obligations to adhere to prices set by OPEC. (Paradoxically, Nigeria’s lack of refining capacity meant that it also continued to import petroleum products and suffered consumer shortages.) On the global stage, the New International Economic Order made little headway in the face of predictable opposition from wealthier capitalist powers in Europe and North America. As an unprecedented act of resource sovereignty, OPEC’s intervention represented the high tide of anticolonial internationalism. But the economic crisis, which the price hikes created blew the same front apart.

Seeking to plug holes in their development budgets, African governments went borrowing. Money was in plentiful supply: the petrodollars which had flowed into oil producers in the Arab world were first deposited in European and American banks, then recycled as commercial loans. African governments had already begun to test the waters of the so-called ‘eurodollar market’ even before the oil crisis, but the petrodollar influx, financial deregulation, and the desperate condition of oil importing economies accelerated this trend. Routed through offshore banking circuits, this was the very opposite of ‘re-territorialisation’. Even greater sums came in the form of overseas development assistance from foreign governments and international institutions. While these loans kept African economies temporarily afloat, a second energy crisis in 1979 and sudden rise in interest rates plunged the continent into financial crisis. By the beginning of the 1980s, the radical project of the Third World had crumbled. In its place arose the assemblage of indebted states known much more pessimistically as the ‘global South’.

If this history sounds familiar, it is because it shares so much with the story of our own times: the effects of distant conflict on fuel and food supplies, the shifting distribution of geopolitical power, and especially the existential threat posed by ecological disaster. From Kenya’s maandamano to the regional ripple effect of Nigeria’s removal of fuel subsidies, recent events show how external shocks produce moments of reckoning that expose deeper tensions about the distribution of wealth. Diagnoses of Africa’s economic challenges have long foregrounded the era of structural adjustment as a key turning point. Yet the ‘polycrisis’ facing African governments today suggests that engagement with the history of the 1970s, marked by opportunities as well as foreclosures, might be more instructive. As African governments respond to the challenges of the present – scrapping subsidies, securing grain supplies, renegotiating Eurobond debts, and showing global leadership to confront the climate emergency – the experiences of commodity crises past suggest that choices remain available, that international cooperation is essential to realising them, and that such solidarity is far easier to proclaim than to practice.