For generations, Kenyan farmers have tended to their vegetable crops, nurturing the land and providing the nation with a steady supply of fresh, locally-grown produce. However, a recent move by the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) to implement stricter licensing requirements for vegetable growers has sent shockwaves through the agricultural community, raising concerns about the far-reaching implications for the country’s food security and the livelihoods of countless smallholder farmers.

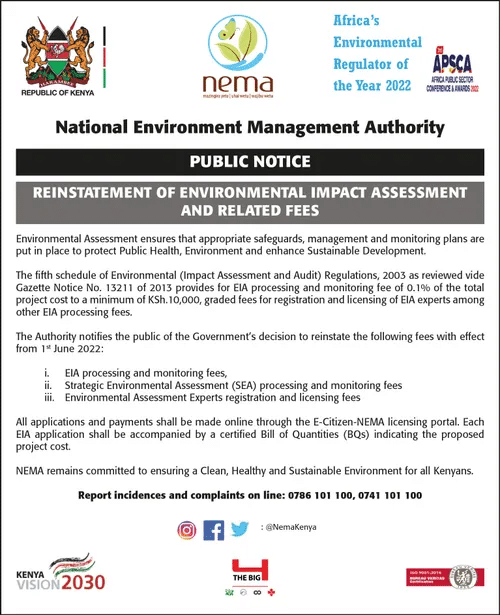

At the heart of the issue is NEMA’s mandate to ensure the sustainable and responsible use of the country’s natural resources, including the soil and water that are the lifeblood of Kenya’s agricultural sector. Under the new regulations, all vegetable farmers, regardless of the size of their operations, will be required to obtain a NEMA license before they can legally cultivate their crops.

“The goal is to protect the environment and promote more sustainable farming practices,” explains NEMA Director General, Dr. Kariuki Muigua. “By requiring farmers to undergo soil testing and adhere to strict guidelines on the use of pesticides and other inputs, we hope to minimize the negative impact of vegetable production on the land and surrounding ecosystems.”

However, for many smallholder farmers, the prospect of navigating the bureaucratic hurdles and the financial burden of obtaining a NEMA license has sparked a sense of trepidation and uncertainty.

“This is a huge challenge for us,” laments Fatuma Otieno, a vegetable farmer from Kiambu County. “Most of us simply don’t have the resources or the technical expertise to undertake the soil research and comply with all the regulations. It’s going to be a massive financial and administrative burden that many of us may not be able to bear.”

Indeed, the requirement for farmers to conduct comprehensive soil testing and analysis before they can receive their NEMA license has emerged as a particular point of contention. While the importance of understanding soil health and optimizing nutrient management is well-recognized, the cost and logistical complexities of these assessments have become a significant barrier for small-scale producers.

“The soil testing alone can cost upwards of 20,000 shillings per plot,” explains Otieno. “That’s a huge investment for us, especially when you consider that many of us are already struggling to make ends meet. And then there’s the time and effort required to collect the samples, coordinate with the labs, and navigate the paperwork – it’s just overwhelming.”

The implications of these new NEMA regulations extend far beyond the individual farmer, however, with concerns that the cumulative impact could have a devastating effect on the country’s overall vegetable production and food security.

“We’re talking about millions of Kenyan farmers, many of whom are the backbone of our domestic food supply,” warns agricultural economist, Dr. Esther Wanjiku. “If a significant portion of them are priced out of the market or forced to abandon vegetable farming altogether, the ripple effects could be catastrophic. We could see shortages, skyrocketing prices, and a greater reliance on imported produce – all of which would undermine our national food sovereignty.”

Moreover, the NEMA licensing requirements have raised concerns about the potential for further marginalization of already vulnerable farming communities, particularly those in remote or resource-poor areas.

“This isn’t just about the financial burden,” says Otieno. “It’s also about the access to information and the technical support. Many of us, especially the smallholder farmers in the rural areas, simply don’t have the same level of exposure or the connections to navigate this process effectively. We’re at risk of being left behind.”

In response to these mounting concerns, the Kenyan government has acknowledged the need for a more nuanced and collaborative approach to implementing the NEMA regulations. Efforts are underway to explore ways of easing the financial burden on smallholder farmers, potentially through the provision of subsidies or the establishment of communal soil testing facilities.

“We recognize that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be the most effective solution,” says Agriculture Cabinet Secretary, John Mwangi. “We’re committed to working closely with the farming community, NEMA, and other stakeholders to find ways of balancing environmental sustainability with the realities and needs of Kenyan smallholder producers.”

As the debate around the NEMA licensing requirements continues to unfold, the stakes have never been higher for the future of Kenya’s agricultural sector and the food security of its people. The coming months and years will be a critical test of the government’s ability to navigate this complex issue, striking a delicate balance between environmental protection and the preservation of the livelihoods that are the backbone of the nation’s agricultural economy.

“We can’t afford to get this wrong,” warns Wanjiku. “The future of our food system, our rural communities, and the very sustainability of our land depends on finding a solution that works for everyone. It’s a challenge, to be sure, but one that we must rise to meet, for the sake of all Kenyans.”