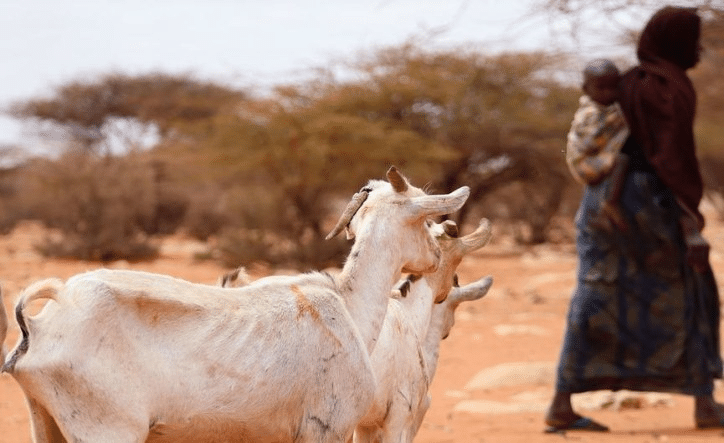

Climate change poses a daily struggle in Kenya despite its minimal contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions. Severe challenges, including heatwaves, erratic rainfall, and frequent floods, impact lives and the economy. Annually, climate change cuts nearly 5% from Kenya’s GDP, particularly affecting agriculture and water resources, which make up a third of the economy. By 2050, this loss is expected to triple. Small-scale, rain-dependent farms, predominant in over 80% of arid and semi-arid lands, face devastation, exacerbated by poor infrastructure. This narrative extends beyond Kenya, highlighting a common thread across Africa and the developing world.

The solution lies in wealthy, high-emission nations assisting less affluent nations. Developing countries must enforce strict regulations, invest in renewables, and actively engage in global climate agreements to fulfill their responsibilities. Neglecting this duty not only harms the environment but also impedes global sustainability efforts, particularly in Africa.

A new dawn for climate justice may have arisen at COP28 in Dubai late last year. The climate summit announced the landmark decision to approve a Loss and Damage Fund through which wealthy states will compensate poor states for the irreversible harms of climate change. Initial commitments totaled $700 million.

This fund is crucial for Kenya, a nation grappling with the ravages of climate change. However, caution is warranted as the details of this new financial mechanism are worked out.

Firstly, concerns arise about the potential exclusion of countries like Kenya due to the choice of the World Bank as the interim fund. The World Bank’s classification of Kenya as a lower-middle-income country may make it harder for the government to access a fund designed to assist the most vulnerable countries. A nuanced approach is needed to ensure funds are allocated based on climate vulnerability and impact rather than purely on income classifications. On-the-ground reporting and models predicting which countries are most vulnerable to climate change impacts will be important.

Secondly, historic experiences with the World Bank have often led to greater dependence rather than building resilience. Conditions attached to loans, such as austerity measures, undermined the objectives of finance by restricting fiscal space. Most climate finance is also in the form of loans. Policymakers must learn from the past and ensure a different approach to the Loss and Damage fund, prioritizing grants over loans to empower countries without burdening them with additional debt.

Finally, the committed amount by developed nations to the Loss and Damage Fund so far is insufficient compared to actual climate financing needs. A study estimated that low- and middle-income countries experience over $2.1 trillion in produced capital losses due to climate change, and developing countries need approximately $400 billion annually to address these losses. The initial $700 million pledges fall short of broader COP28 commitments expected to provide about $100 billion per year by 2030.

The Loss and Damage Fund is only a part of the broader climate finance challenge, and its success depends on continuous commitment and effective distribution of resources. It is a small step towards addressing the imbalance where countries least responsible for climate change face its harshest consequences.

While foreign aid is necessary, sustainable alternatives are emerging across the continent, such as Tanzania’s adoption of solar power systems and Kenya’s significant investment in renewable energy sources. These efforts are crucial for building resilience against climate threats. The international community’s support, as seen in the Loss and Damage Fund, is vital for amplifying these efforts and ensuring they can be sustained.

The establishment of a Loss and Damage Fund at COP28 is about more than financial assistance; it is a recognition of the disproportionate impact of climate change on vulnerable nations. It is a commitment to climate justice, ensuring that those who have contributed least to the crisis are not left to face its consequences alone. This fund represents not just financial aid but a symbol of global solidarity in the fight against climate change. It is a step forward, but the urgency and scale of the climate crisis demand that this momentum is not only maintained but accelerated.

By Kalonzo Musyoka